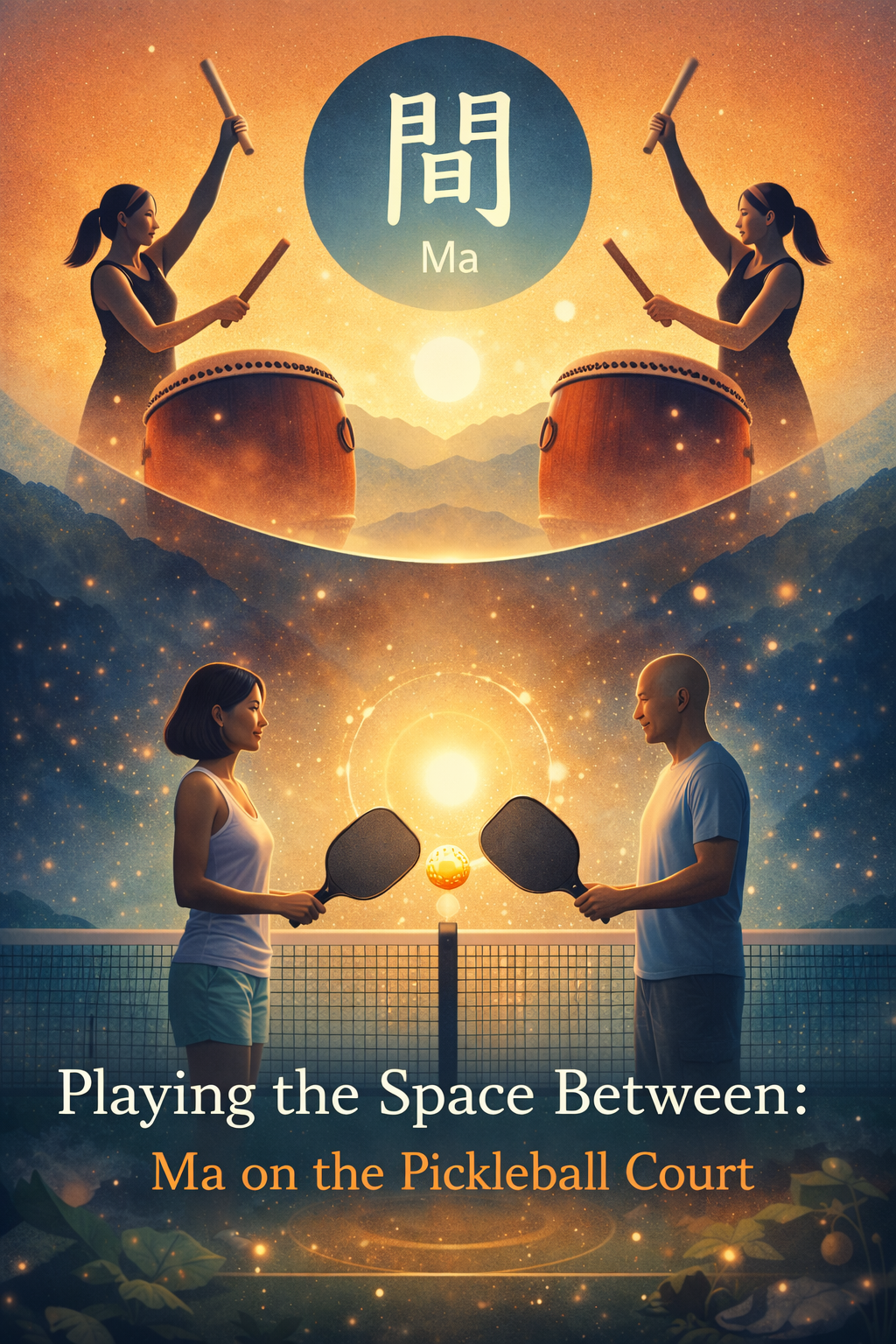

I first learned about the Japanese philosophy of Ma from my taiko drumming teacher. The first time I watched a taiko performance, I found myself deeply moved at a vibrational level—the power of witnessing Asian women on stage taking up space, being loud in a way that wasn’t noise or chaos. What made it so powerful was not just the sound of the drums, but the space around them: the pauses between strikes, the stillness before movement, the silence that amplified what came next. It was loud in an intentional, rhythmic way—artful and magical. Vibrational. Life-giving. A quiet loudness, if you will—where Ma, the space between, gave the sound its depth and power.

Now, I find myself reflecting on how Ma is showing up in the game of pickleball—a sport I have come to love deeply on physical, mental, emotional, and social levels. A sport where I have built a community of friends. A sport where the younger, competitive athlete in me is once again able to come alive.

The Japanese philosophy of Ma teaches me to pay attention to what exists between things—the pauses, the intervals, the spaces that are often overlooked yet quietly shape the whole experience. Ma is not emptiness; it is living space, full of information and possibility. When I bring this awareness onto the pickleball court, the game changes. It becomes less about constant action and more about presence, timing, and relationship.

Ma is not emptiness; it is living space, full of information and possibility.

I notice Ma first in how I position myself on the court. When I stop rushing to cover every inch or reacting out of urgency, I begin to sense where I actually need to be. Holding the kitchen line without crowding it, creating space as the ball approaches, and allowing discernment to arise—whether to take the ball out of the air or let it bounce—keeps me in right relationship with the moment. Staying attuned to my partner’s position and movement deepens this sense of spatial harmony. When I honor these spaces, my body feels more balanced, my shots more intentional, and the game unfolds with greater ease.

One of the most profound places Ma shows up for me is in the tiny space between my paddle and the ball just before contact. There is a moment—brief, subtle, and easy to miss—where I can choose presence over reflex. When I stay with that moment, I feel my grip soften, my breath steady, and my awareness widen. I’m no longer just hitting the ball; I’m meeting it. That sliver of space shapes everything that follows. My dinks land with more touch, my resets carry less tension, and even my drives feel cleaner and more aligned. The quality of the shot is born in the pause before impact.

Timing, I’ve learned, is another expression of Ma. Pickleball constantly invites me to swing harder or faster, but Ma reminds me that waiting can be just as powerful. When I allow the ball to drop, when I pause instead of forcing a shot, I often disrupt my opponent’s rhythm without doing anything dramatic. The pause creates uncertainty for them and clarity for me. In those moments, I feel less rushed and more in conversation with the game.

The philosophy of Ma becomes especially alive in the dynamic and fluid space between partners. Good doubles play isn’t about standing close or far—it’s about sensing what the moment calls for. That space breathes. Sometimes it narrows as we move together toward the kitchen line; sometimes it widens to cover angles. When we honor that space, an intuitive knowing emerges about how best to cover the court. We begin to move as a unit, trusting the shared space we are co-creating. The partnership feels more fluid, more artful.

Ma also supports me emotionally and shapes my mindset. Pickleball can be fast, charged, and competitive, and it’s easy to carry frustration from one point into the next. Practicing Ma internally means creating space between what just happened and what is happening now. A breath. A softening of my jaw or shoulders. A reminder that the next point is its own moment. As Roger Federer says in his 2022 commencement speech at Dartmouth College, “it’s just another point.” That inner pause helps me return to presence instead of reaction—letting go of the last point and allowing me to play with steadiness even when things don’t go my way. It also gives me the capacity to offer myself, and my partner, grace when we make an unforced error or send a ball into the net that, in our minds, should have been an easy put-away.

When I play with Ma in mind, pickleball becomes more than a game of speed and strategy. It becomes a practice of awareness—of space, of timing, of relationship. From the moment between paddle and ball, to the dynamic and fluid space between partners, to the pause that steadies my mind, Ma teaches me that what I leave open is just as important as what I do. In honoring the space between, I find greater control, deeper connection, and a quieter, more joyful, and more spacious way of playing.

And some things to consider:

The next time you step onto the court … a pickleball court, a tennis court, the court of your life both personal and/or professional, or as you practice a musical instrument …. notice the spaces you usually rush past.

Where might a pause offer you more choice—before contact, between shots (or choices and actions), or after a point?

How does honoring space change your relationship to your partner, your opponents (or new habits and practices where you uncover resistance), and yourself?

I have discovered that my most profound lessons in life, and on the court, and where I have learned to become more skillful in navigating the complexities and challenges of life has not been not in what I add, but in simply what I allow to emerge.

How might embracing Ma and the practice of pausing open new possibilities in your life?